Introduction

Randonneuring is not just a sport; it’s a journey of endurance, discovery, and personal growth. It’s where the open road becomes a test of both body and mind. Pushing you beyond the limits of typical cycling. My journey into randonneuring began with a simple curiosity about long-distance riding. It quickly evolved into a passion that has taken me across countless kilometers. Through day and night, in pursuit of that unique blend of challenge and freedom that only randonneuring can offer. It started a bit before Covid. And quickly expended when cycling became the only way to replace the adventure of traveling.

One of the most memorable experiences was the Paris-Brest-Paris (PBP) 2023. A 1,219 km odyssey that stands as a pinnacle in the world of randonneuring, it’s the halo event. The grandfather of them all. This event was more than just a ride. It was a testament to meticulous preparation, mental fortitude, and the camaraderie of fellow cyclists. In the months leading up to PBP, every training ride, every gear choice, and every route planning session became crucial pieces of the puzzle that would eventually lead to success.

But the road to becoming a randonneur is paved with more than just epic events like PBP. It includes the lessons learned from Randonneur Super Series, 200-300-400-600 km Brevets, where mental resilience is as vital as physical endurance. It’s in the countless smaller rides that prepare you for the big ones. Each offering its own set of challenges and rewards.

Randonneuring or Audax are officiated by Audax Club Parisien, the official organisers of Paris-Brest-Paris every four year.

In this guide, I aim to share the wealth of knowledge accumulated through my experiences. Providing you with practical advice, personal anecdotes, and essential gear recommendations. Whether you’re a seasoned cyclist looking to take on longer distances or a beginner just starting out, this guide is designed to help you navigate the world of randonneuring with confidence.

Understanding the Rules and Culture

Randonneuring is a unique cycling discipline, distinct not just in its long distances but in the culture and ethos that underpin it. Unlike competitive cycling, where speed and placement are paramount, randonneuring prioritizes personal achievement, self-sufficiency, and camaraderie. The root of this sport are in the idea of endurance as a shared journey. Rider’s goal is not to outpace others, but to complete the challenge within the prescribed time limit, often in the company of newfound friends.

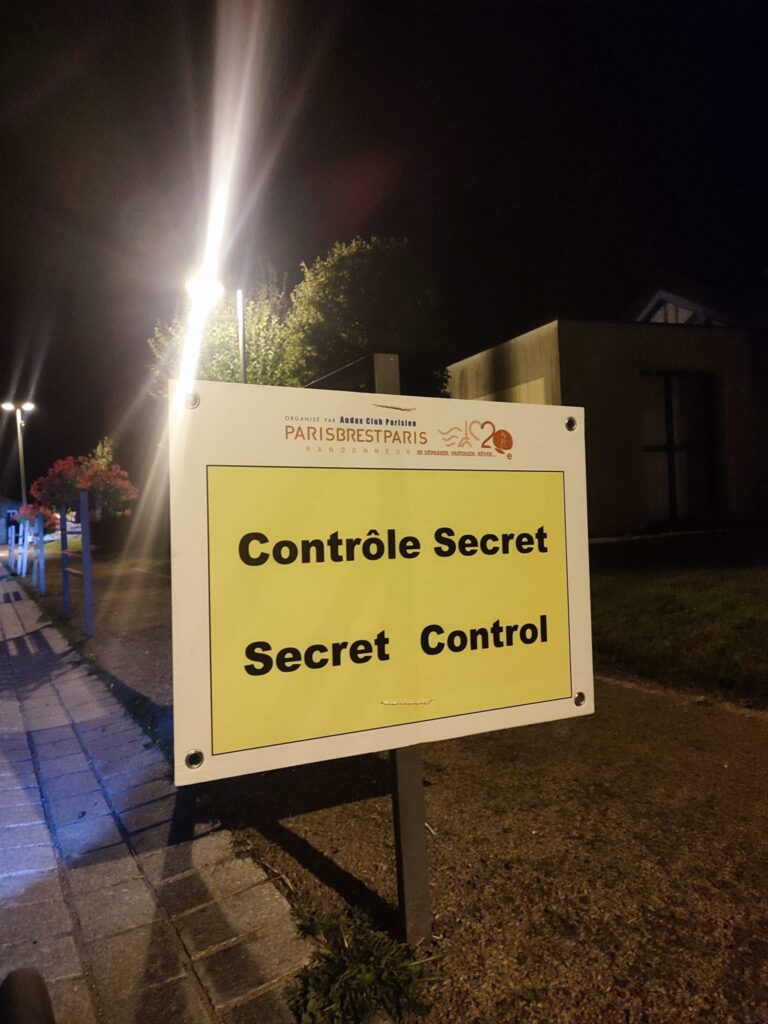

One of the most defining aspects of randonneuring is the emphasis on control points. These are mandatory stops along the route. Riders must check in, often by having a brevet card stamped. These control points serve several purposes: they ensure that riders follow the correct course, provide opportunities for rest and refueling, and offer a chance to connect with other randonneurs. Time at these controls is as important as the riding itself, where riders share stories, discuss strategies, and exchange encouragement.

Time limits are another cornerstone of randonneuring. Each brevet has a set time limit that corresponds to the distance. For example, a 200 km brevet might have a 13.5-hour limit, while a 600 km brevet could allow up to 40 hours. These limits are generous, but they require riders to maintain a steady, sustainable pace. The challenge is not in riding fast, but in riding smart—managing your energy, time, and resources over long distances. My experience during the Paris-Brest-Paris highlighted how critical time management is. It’s not just about riding; it’s about planning your breaks, anticipating your needs, and keeping an eye on the clock without letting it dominate your ride.

Randonneuring also demands a high level of self-sufficiency. Riders must be prepared to handle mechanical issues, navigate the course, and manage their nutrition and hydration without external support. This aspect of the sport fosters a deep sense of independence and resilience. During my 600K BRMs, for instance, I encountered several challenges—from unexpected weather changes to mechanical issues—that required quick thinking and self-reliance. These experiences reinforced the importance of being prepared for anything, both mentally and physically.

The culture of camaraderie in randonneuring is unlike any other. While each rider is ultimately responsible for their own ride, there’s an unspoken code of support among randonneurs. Whether it’s sharing a spare tube, offering words of encouragement, or riding together through the night, the bonds formed on these long rides are strong. The friendships I’ve made during events like the PBP are as enduring as the memories of the ride itself. These connections, forged through shared challenges and mutual respect, are what make randonneuring not just a sport, but a community.

Training for Long Distances

Effective training for randonneuring requires a deliberate and structured approach, focusing on gradually building physical endurance and mental resilience. One of the key strategies I employed while preparing for the Paris-Brest-Paris (PBP) was systematically increasing my ride distances over time. Starting with manageable distances and incrementally extending them allowed my body to adapt to the physical demands of long-distance cycling.

Equally important is simulating brevet conditions during training. This means incorporating night rides, as riding in the dark requires a different skill set and comfort level. Night riding taught me the importance of managing fatigue and maintaining focus when visibility is limited and the body’s natural rhythms are disrupted.

Training in various weather conditions is another critical aspect. This is why I ride my bike to work all year long. Wearing shorts in the summer, or riding on the snow. Randonneuring events often span several hours or even days, during which weather can change drastically. By intentionally riding in rain, wind, and cold, I learned to handle these challenges effectively. Over time, such experiences helped me develop strategies to conserve energy and stay motivated, even in less-than-ideal conditions.

Pacing is a crucial skill in randonneuring, one that I refined over numerous long rides. It involves finding a sustainable rhythm that allows you to cover long distances without exhausting yourself prematurely. I focuse on maintaining a consistent pace, ensuring I have enough energy reserves for the later stages of the ride. Taking strategic breaks, especially during longer brevets, is vital for recovery and preventing burnout.

Nutrition and hydration strategies are equally important in training. Experimenting with different foods, drinks, and timing during training rides helped me discover what worked best for my body. Consuming the right amount of calories and staying hydrated is crucial for sustaining energy levels during long-distance events.